The last of the Naga headhunters

18 Aug 2018

A recurring theme of our photographic explorations is vanishing cultures and ways of life. We don’t seek it out: it ups and smacks us in the face as we enquire, poke, prod and weasel our way into villages and tribes in search of good stories and fine camera-fodder. And in particular, when we revisit a location and find that life has moved on, along with some of our subject material.

Nowhere is the clash of human progress and ancient ways of life more keenly felt than in Nagaland, India. When we last visited, I was immediately struck by parallels with sights we’d witnessed a few hundred kilometres south along the Patkai mountains, in amongst the tattooed mountain tribes of western Myanmar.

The Naga tribes are a mountain diaspora of some 66 groups, 17 inside Nagaland itself and some more assimilated into mainstream India than others. Speculation has it that they appeared in India around a thousand years ago, originating from Mongolia, China or some southeast Asian enclave. The Naga folk never quite managed to create their own country: they were natural marauders, attacking and pillaging other Naga tribes and invaders in raids and skirmishes that produced lots of bloody body parts and trophy human skulls. When the Brits came along and stuck their flag in Naga territory in the early 19th century, the tribespeople eagerly took on the European colonists.

Bringing home the heads of one’s enemies was a major prestige-winner, a rite of passage that earned coveted facial tattoos and other badges of male honour. Their temporary British overlords banned the practice, but it continued: the last human head trophy is said to have been taken in 1960.

In the photo set at the top of this article you’ll see men — rather old men — bearing the fierce ornamentation and face-marks of their battlefield successes, strength and virility. Behind this fading braggadocio, there is painfully little giving them social traction in the 21st century. Secessionist insurgencies have come and gone, and peace thankfully reigns with the tribal leadership settling pragmatically for a measure of autonomy as a state within a thriving India.

The Naga hunting grounds are beautiful, mountainous, verdantly forested — but as hunting grounds they’re depleted through generations of indiscriminate depredations and challenged by tough new government conservation laws.

The Naga hunting grounds are beautiful, mountainous, verdantly forested — but as hunting grounds they’re depleted through generations of indiscriminate depredations and challenged by tough new government conservation laws. The laws outlaw hunting but are widely flouted thanks to ownership of the Naga forests falling overwhelmingly into the hands of individuals or communities, outside the government’s direct control, and through cultural values that enshrine the right to take wildlife at will.

The real cultural threat, though, has little to do with politics and territory. As we see in so many other remote cultural outposts, the youngsters in these photos will almost certainly be charmed away from their families, villages and culture by the bright lights, smartphones and trendy lifestyles of the nearest cities — Kohima, Dimapur, or even the teeming metropolises of Kolkata and Delhi.

And the old men and women will fade away in a cloud of opium, a haze of cheap rum, and rheumy reminiscences by smoky campfires.

Shoot this with us:

More India backstories and galleries…

Dancing with the gods

We embed ourselves in an elusive Hindu monastery and uncover dancing monks who draw on millennia-old epics for their storytelling performances.

1st October 2019

Northeast India: With the water buffalo Photo Gallery

What's on our camera backs today? We're with water buffalo in northeast India, following semi-nomadic herdsmen as they drive their beasts across the terrain, fighting flying pests with fire.

12th April 2019

Bengal’s brick kiln kids

In West Bengal, India, a brickyard tour uncovers striking photographs as well as unexpected truths about human motivation and migration.

5th April 2019

Smoke on the water

Assam, India, is so rich with people opportunities that sometimes it's hard to just stop and admire the scenery. We're glad we did.

29th March 2019

Majuli waterscapes Photo Gallery

A collection of images and opportunities from the river island of Majuli, in Assam, India.

18th March 2019

Delhi’s Yamuna – a toxic beauty

A Delhi photo tour takes in the sad state of the holy Yamuna river, and reflects on the unexpectedly positive outlook of many of its riverside dependents.

1st March 2019

Tea and tattoos

We stop for a cuppa with the Apatani tribe of Arunachal Pradesh and talk about their fading facial adornment and customs.

18th February 2019

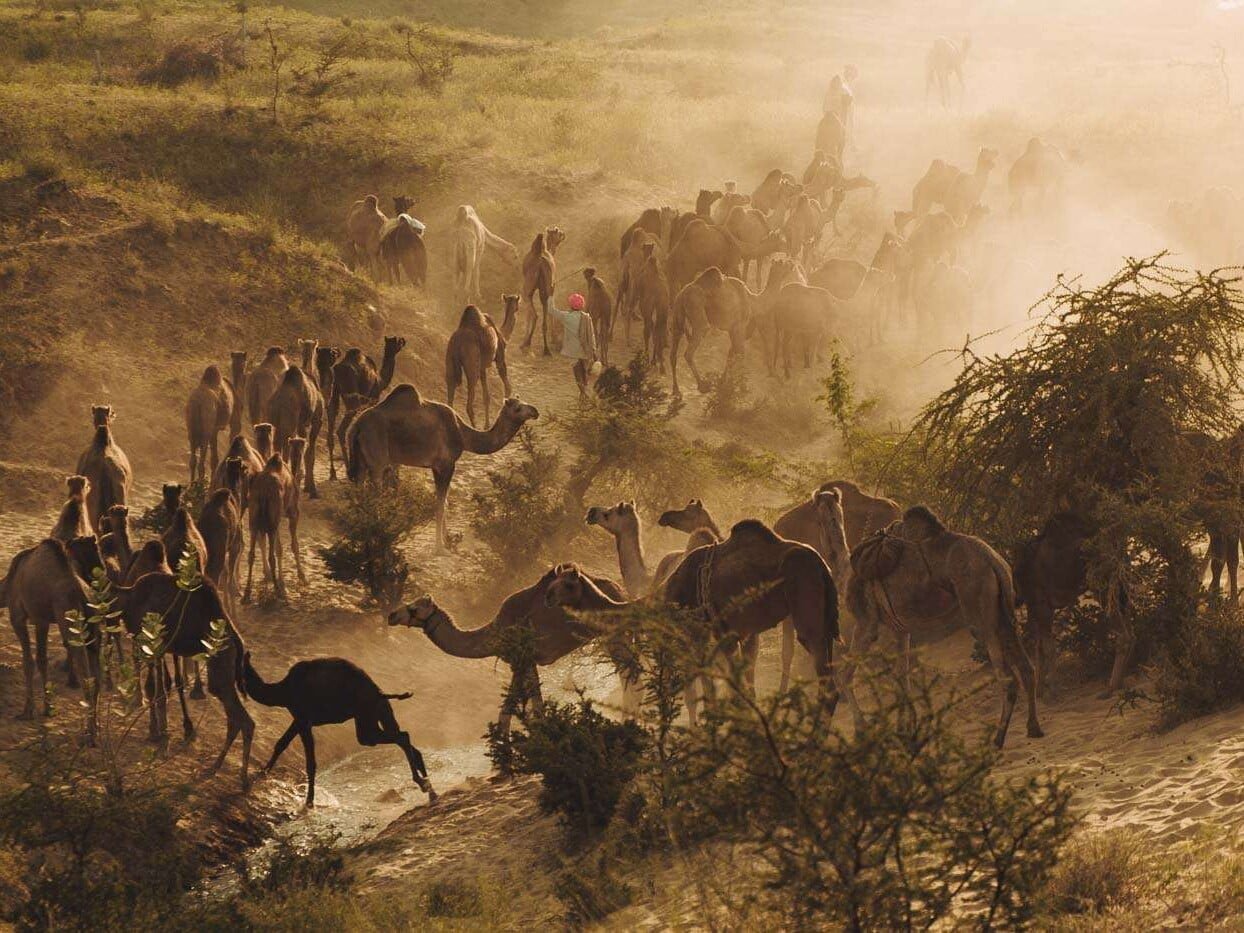

Pushkar Camel Fair and Rajasthan Photo Gallery

A collection of images and opportunities from Rajasthan, India, taking in the Pushkar Camel Fair.

23rd December 2018

Varanasi and Agra – Photo Gallery

A collection of images and opportunities from two iconic Indian destinations.

16th December 2018

Fishing with the Mishing

Gone shootin': We join Majuli's Mishing fishermen on a foggy morning and return home with a splendid catch.

1st October 2018

A dark and magical place

On a shrinking river island in the Brahmaputra, the dark beauty of the the Vaishnavite monasteries keeps alive a centuries-old tradition of worship.

30th September 2018

What’s cooking?

We drop in on one of our favourite Rajasthan villages to meet old friends over supper. Just happened to have our cameras handy…

28th September 2018

Shrouded in time

As the ghunghat or veil becomes increasingly criticised across modern India as a vestige of an oppressive past, we look at its bright side.

25th September 2018

Medicine man

An amble through a Rajasthan desert hamlet unexpectedly gets us up close and personal with a faith-healer.

23rd September 2018

Shapeshifters

The Bahurupi people are the proverbial quick-change folk artists. Ironically, change is catching up with them.

11th September 2018

Taches and turbans

A face-to-face photo-romp through Rajasthan, India, where beards, mustaches and turbans are taken mighty seriously.

8th September 2018

Ladakh in Winter Photo Gallery

A collection of images and opportunities from Ladakh in winter, amidst the Himalayan and Karakoram mountain ranges.

25th February 2018

Shooting Diwali in Rajasthan

As Pushkar Camel Fair becomes overloaded with photographers, timing is everything…

19th January 2018

Gujarat encounters: Where I go, my radio goes

In Gujarat, India, we run into a radio-crazy Ahir farmer with a shrewd grasp of world affairs.

19th May 2017

Angry birds: India’s bloody cockfighting business

Revered by many and reviled by others, cockfighting thrives in India.

5th May 2017

Paydirt: Shooting India’s Kushti wrestlers

There's photographic gold in India's dirt wrestling tradition – Kushti.

1st May 2017

Ladakh in Summer Photo Gallery

A collection of images and opportunities from Ladakh in summer, amidst the Himalayan and Karakoram mountain ranges.

22nd February 2017

India’s chai: The cup that cheers

India's roadside tea stalls are an eye-opening experience for photographers and tea-lovers.

7th January 2017

Ladakh: A study in contrasts

A photograph from our Ladakh photo tour prompts thoughts on contrast, photographic and otherwise.

26th November 2016

Five o’clock stubble

A little planning and a lot of luck gives us some shooting fun amidst burning stubble on an Assam tour…

28th May 2016

In God’s name: India’s Ramnami

Devotion, defiance and full-body tattoos… the vanishing way of life of this Hindu sect in India.

22nd May 2016

Varanasi: A matter of life and death

Varanasi's photography tour opportunities are extraordinary — and occasionally overwhelming…

15th April 2016

Visiting old friends in Ladakh

Shoot Director Sridhar reflects on shared moments with an old friend in Ladakh, India.

22nd March 2016

Sub-zero shooting adventures in Ladakh’s winter

It's cold but it's really hot: stunning opportunities on our new Ladakh Winter Photography Tour.

11th March 2016

Bleary-eyed sessions in a Nagaland dope den

We join in with the locals in a rum-and-opium party in Nagaland. High times in low light.

23rd February 2016

Village encounters in deep Rajasthan

On the road to Pushkar Camel Fair, we find a Rajasthan desert hamlet with pleasant photographic surprises on every corner…

13th February 2016